In the global chips race, EU’s cash engine sputters

The European Union is scrambling to cough up the public investment needed to try and go head-to-head with the world's leading chip producers in the United States, Taiwan and South Korea.

Europe is aiming to grab 20 percent of the global market share in microchips by 2030 with the European Chips Act, one of the EU's most ambitious industrial policies to date.

But a cornerstone of its budget is in question this week with both European Parliament lawmakers and European government officials quarreling over how to pay for the new chips push. And that risks torpedoing the whole plan.

Europe is trying to enter a global race to expand local microchips manufacturing, design and innovation. It's also trying to learn the lessons of a chips shortage over the past two years that shuttered European car plants and held back sales of consumer electronics. At the same time, chips are a new battleground for a geopolitical Cold War between the U.S. and China.

The European Commission talked big earlier this year by saying there would be €43 billion of public investment to back the EU's chip dreams. But even from the start, the EU executive struggled to explain just how that funding would come together.

That funding is now facing a whirlwind of questions and concerns in Brussels, as the Parliament and Council scrutinize the chips budget amid a push to get the legislation passed as soon as possible. That seems to be slowing down; crucial deliberations by government representatives have been scrapped from this week's agenda, underlining the difficulty in getting a deal.

Eva Maydell, a center-right member of Parliament, told lawmakers on Monday of the importance of making progress on chips money even as she seeks clarity from the Commission on the budget "in order for our promises to become reality and not castles made of sand."

"We cannot ignore the significant level of investment that our global competitors and partners are putting in similar initiatives," she said.

Cooking the books

Most of Europe's overall investment in the semiconductor industry will be subsidies from national governments that aim to lure private investment.

The EU's planned €43 billion framework included an €11 billion pledge to help bring research applications to the market. It was going to pay for it by taking €3.3 billion out of the EU budget. Half of that €3.3 billion would be taken from the EU's flagship R&D program Horizon Europe and half from its digital technology program Digital Europe.

European lawmakers are up in arms, warning that the EU's chips plans are eating away at funding for other potential projects. Parliament's lead member on the issue Karlo Ressler said it's "unfortunate" that the chips budget is based on taking money from elsewhere.

MEP Eva Maydell told lawmakers of the importance of making progress on chips money

MEP Eva Maydell told lawmakers of the importance of making progress on chips money

Last week a group of lawmakers led by Maydell wrote to the Commission asking for "a detailed projection of funding available," writing that "there's increasing concern that the purported sums of funding available to support the ambition of the Chips Act may not materialize."

Countries at odds

The Chip Act's budget is a headache for EU countries too. Deputy ambassadors this month struggled with it as one of the three remaining open issues in the draft bill they are negotiating. Some capitals are worried that other research projects will fall victim to the chips rush, one EU diplomat said.

The destination of the chips cash is also raising hackles. Chipmakers are placing their projects in larger EU nations such as Germany and France, which can guarantee the public support needed to make the new investments happen.

"People are waking up to the reality that allowing member states to finance industry projects through national subsidies massively tips the scale towards big member states," said Niclas Poitiers, a research fellow at Brussels-based think tank Bruegel.

The Czech Republic, which currently lead talks between EU governments, had aimed to nail the Chips Act at a December 1 meeting of industry ministers. That seems unlikely now; at best they could do a deal on the legislation by excluding the budget issue, effectively kicking the can down the road.

The global race that wasn't

The EU's €3.3 billion from the research budget is dwarfed by funding from EU governments which could be as much as €30 billion.

Europe's struggles to secure proper funding for chips give the lie to its geopolitical posturing and efforts to restore chip production. The U.S. CHIPS Act became law in August and the U.S. federal government has far more power over how it can spend its $52 billion budget.

The real race now is how well regions can pull in new investments for "mega fabs" from three key manufacturers of chips: Taiwan's TSMC, South Korea's Samsung and the U.S.'s Intel.

Europe has secured €17 billion from Intel for a German plant and a reported €5.7 billion from smaller manufacturers STMicroelectronics and GlobalFoundries in France. The U.S. has been much more successful. Just last week, Bloomberg reported that Taiwan's TSMC — the industry leader — was laying the groundwork for a second U.S. factory in Arizona, next to its first.

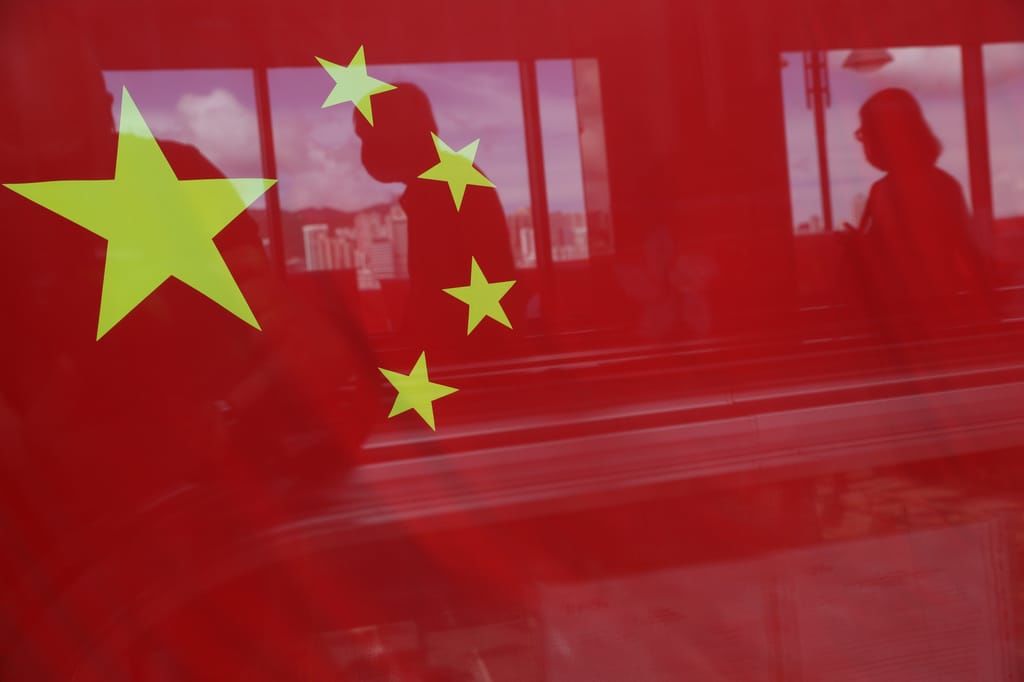

China is on course to invest $150 billion in chips between 2015 and 2025

China is on course to invest $150 billion in chips between 2015 and 2025

China is on course to invest $150 billion in chips between 2015 and 2025, the Commission estimated last year. South Korea is working with industry players to unlock $450 billion of private funding by 2030.

The Chips for Europe Initiative's €11 billion focused on commercializing research "would still punch below its weight" even if it all materializes, said Zach Meyers, a senior research fellow at London-based think tank Centre for European Reform. Meyers estimates that the U.S.'s chips strategy promises $13.2 billion in research.

Even that small bet has the potential to hit a jackpot.

"If we look at how the U.S. uses chips as a geopolitical tool, it's all about the [intellectual property], the IP rights for technology," Poitiers said.

"The objective should be to develop some technologies that no one else has. For developing these technological advantages, we need to invest in research," he said.